I think of Josh Billings as an old-timey version of Dave Barry, except with better hair.

Billings was sort of a big deal in the late 1800s. Known for his home-spun whimsy, Billings was a Will Rogers before Will Rogers invented Will Rogers. Billings was considered a contemporary of Mark Twain, but Billings had a gimmick: he wrote his whimsical maxims and essays phonetically, in a strained goober vernacular.

Sixty years after dropping dead in Monterey in 1885, Billings resurfaced as an unfortunate character in one of John Steinbeck’s most endearing books, “Cannery Row.” And, thanks to Steinbeck, Billings nowadays might best be remembered because of the circumstances of his death, and especially the disposal of his entrails.

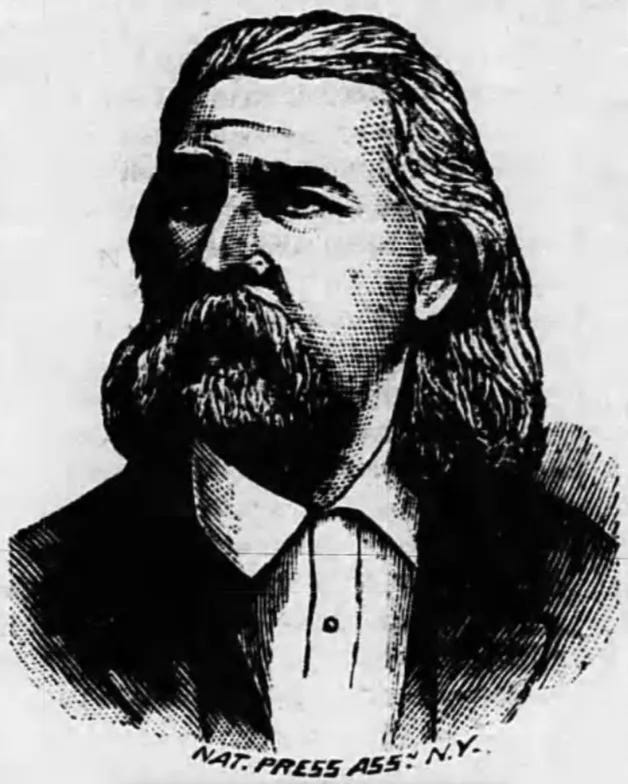

Up until his death, newspapers ran his cornball essays and he drew SRO crowds on the lecture/comedy circuit. With few other entertainments available in those bad old days, America’s local yokels settled for the famous wits who showed up in theaters and grange halls to pontificate a certain brand of rustic philosophy. Josh Billings was a star, a massive presence on a stage with his long flowing locks and his off-hand charm.

He found himself in Monterey, at the age of 67, after his doctor prescribed a trip to the West Coast to clear up a persistent case of vertigo. He took residence at the posh Hotel Del Monte, from where he based a careful tour of cities throughout Northern California. He had been an agreeable addition around town; the locals basked in his presence and he spent much of his spare time in the hotel lobby, where he engaged visitors in lively banter.

Around 9:30 a.m. on Oct. 14, 1885, the Monterey physician J.E. Heintz was called to the hotel to tend to Billings. The humorist had felt an odd pain in his chest but he was conscious and he seemed as flamboyant as ever. He was sitting in a chair in the vestibule when the local physician arrived. “My doctors in the East ordered rest of brain,” Billings reportedly told the doctor. “But you can see I do not have to work my brain for a simple lecture; it comes spontaneously.” According to popular accounts, Billings then threw his hands over his head and fell over backwards, unconscious. He died as he was carried to his room.

The cause of death was attributed to “apoplexy.”

News of Josh Billings’ demise spread far and wide. He was remembered fondly, with dozens of important essays describing the Billings legacy and how his brand of philosophy had changed the essence of humor in America. The Weekly Mercury in Oroville weighed in by declaring that if “there is a heaven for humorists, he will rest among its most honored saints.”

But he was largely forgotten as new generations evolved into 20th century sophistication, and it wasn’t until John Steinbeck related an awful story about Josh Billings’ offal in Chapter 12 of “Cannery Row” that most Americans remembered he existed at all. Steinbeck authorities can’t say for certain if the story is true, and the mystery is shrouded in the knowledge that “Cannery Row” is a work of fiction, but it featured characters and events that were easily identifiable when it was published in 1945.

In describing Monterey in “Cannery Row,” Steinbeck noted that it took much pride in its “literary tradition,” referring to Robert Louis Stevenson and the authors in Carmel. But, Steinbeck wrote that Monterey “was greatly outraged over what the citizens considered a slight to an author.” And that author was Josh Billings.

Steinbeck noted that a doctor maintained an office adjacent to what we now know of as Hartnell Gulch, about where the Post Office is today. The doctor “handled all the sickness, birth, and death in the town.” He also worked on animals. And because he had studied in France, the doctor dabbled in the new practice of embalming bodies before burial. Though Steinbeck does not name him, the doctor is presumably Dr. Heintz, the aforementioned French physician who arrived in in Monterey in late 1877 or early 1878.

Steinbeck described how one of his protagonists, a character he refers to in “Cannery Row” as “Mr. Carriaga,” had one day come upon a small boy and his dog struggling up the gulch near the doctor’s office. The boy carried a liver, while the dog dragged a length of intestine “at the end of which a stomach dangled.” The boy explained that he would be using his discovery to chum for mackerel.

Later in the day, as Mr. Carriaga sat in a tavern and considered what he had witnessed, he asked fellow drinkers if anyone had recently died. Someone mentioned Josh Billings and Mr. Carriaga surmised that the boy and his dog were probably dragging away Billings’ innards.

“Josh Billings was a great man, a great writer,” Steinbeck wrote. “He had honored Monterey by dying there and he had been degraded.”

Several of the men in the bar marched over to the doctor’s office to verify that he had indeed embalmed Josh Billings and disposed of his “tripas” in the creek.

They then marched the doctor down to the beach, where they found the boy as he was loading his fishing gear and Billings’ liver into a boat. The dog had apparently abandoned the intestines in the sand. The men forced the doctor to wash the offal “reverently,” and he later paid the expense of the leaden box that went into Josh Billings’ coffin.

“For Monterey was not a town to let dishonor come to a literary man,” Steinbeck wrote.

Josh Billings was the stage name for Henry W. Shaw, a rather well-to-do gentleman from Massachusetts who was the son of a Congressman and the nephew of the chief justice of the New York Supreme Court.

Billings was a striking presence, tall and handsome, with long flowing locks (which reputedly covered up unsightly scarring to the head) and a hale and hearty voice. He had been a farmer and an auctioneer in the West for more than 20 years of his life before settling in Poughkeepsie, N.Y. He had never written for a publication until the age of 45, when he was asked to write articles for someone who had started a newspaper in town. He wrote 20 essays, for which he was never paid, and the newspaper folded.

But he was tickled one day after reading an essay by Artemus Ward, another humorist of the era, and thought that maybe he should try his hand at humor. So he wrote a story about a mule. At that point, Henry Shaw came up with the Josh Billings pen name, and sent the mule essay to someone he’d met who owned a “funny” publication called Nic-Nac. He continued to write — giving his work away for free for five years — until a Boston editor sent him $1.50 for a rewritten version of the mule essay.

This time, he had fractured up the language phonetically so that a typical line read: “The mule is haf hoss, and haf Jackass, and then kums tu a full stop, natur diskovering her mistake.”

Ha-ha!

He wrote columns, variously named “The Josh Billings Papers,” “Josh Billings’ Spice Box” and '"Josh Billings’ Philosophy.” He published several books and was possibly best known for a recurring publication he called “The Farmer’s Allminax.” He rivaled Mark Twain for turning words into cash.

And when he struggled with his health at the age of 67, his doctor recommended a move to California, suggesting the bracing climate of west coast might help. He performed during his convalescence on the Central Coast.

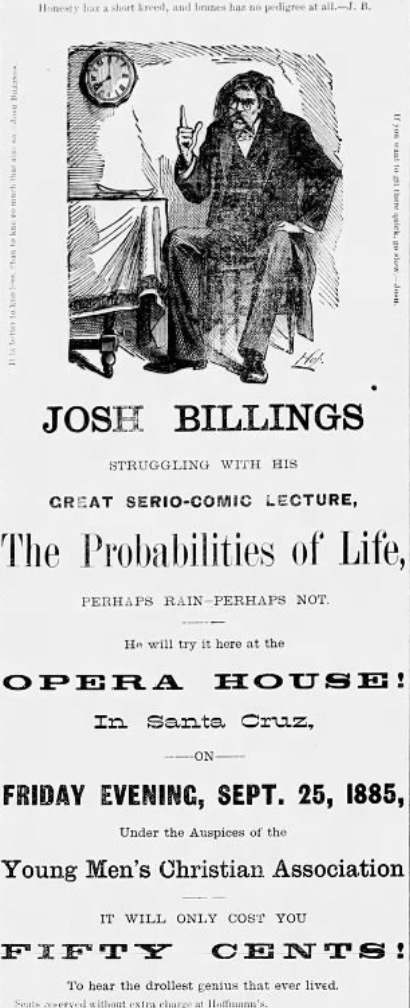

Three weeks before he died, he spent a week in Santa Cruz, staying at the Pacific Ocean House with his wife Zipha. He performed at the Santa Cruz Opera House on the evening of Sept. 25, and would give his final lecture about a week later, in Watsonville.

While in Santa Cruz, he granted an extended interview with a reporter from the Santa Cruz Sentinel for a front-page story headlined “Jovial Josh Billings.” He told the reporter that the doctors sent him to California because they didn’t know what his problem was.

“Doctors don’t know anything,” he told the reporter. “There’s no science in medicine; surgery is a science. Put that down. Medicine’s an experiment, sure’s you’re born.”

He died about three weeks later.

Is Steinbeck’s account of Billings’ postmortem true? Or is it a fanciful tale that Steinbeck embellished? Why would he be so specific about Josh Billings when virtually every other character in the book is given a fictional name? Hoping to get an answer, I asked a handful of local historians and Steinbeck experts.

Historian Tim Thomas, for one, said he thinks “there is a lot of truth to the story. What is true for sure, the Dr./Mortician … lived and worked next to Hartnell Gulch and did indeed dump all the waste and remains into the creek. Not just of Josh Billings, but everyone else as well.”

“I tend to believe it,” said Charles Davis, a Monterey resident and former reporter. “Oft-told tales of Monterey’s wild dogs feasting on offal might easily be chalked up to ‘old wives’ tales,’ but naming Josh Billings as a ‘victim’ and Steinbeck’s talent for gleaning info from old-timers lends it credence.”

Davis points out that, if true, the story is “true irony,” since one of Billings’ most famous aphorisms is "A dog is the only thing on earth that loves you more than it loves itself."

But Geoffrey Dunn, an historian who has collected newspaper clippings from Santa Cruz about Billings’ final performance, said he believes Steinbeck “took literary license with the facts.”

“It seemed to me that Steinbeck was writing about himself there,” he added. The final line in the chapter — “For Monterey was not a town to let dishonor come to a literary man” — was a sarcastic swipe at the locals who had treated Steinbeck so shabbily over the years, Dunn said.

Susan Shillinglaw, perhaps the world’s most prominent Steinbeck scholar, said she can’t say for certain that the story is true. “I don’t know about the offal,” she said. “A great story, but who knows?”

Postscript: En route to its final resting place, the casket containing Josh Billings’ remains was apparently damaged badly on the Union Pacific train. The casket was off-loaded and sent to Omaha, Neb., where undertakers repaired the box. According to reports in the Omaha Daily Bee, the morticians viewed the body to ensure it was still in good shape.

“The face and body were in a remarkable state of preservation, though a thin coat of magnesia placed over the countenance gave it (a) ghastly appearance,” according to the story, headlined “The Dead Humorist.” “The eyes were but slightly sunken and the expression of the mouth was natural and peaceful.”

Fun Fact: An annual triathlon held in the Berkshires of western Massachusetts is named the “Great Josh Billings RunAground.” Now in its 46th year, “The Josh” is named for Billings because the event founders believed one of his wise sayings — “To finish is to win” — was appropriate for the race. “The fun-loving, not-too-serious aspect of the race is why it has become one of the oldest and largest bike-canoe-run triathlons in the country,” according to the race website. “Another Billings quote appropriate to this triathlon is ‘The rare thing a man ever duz iz the best he can.’”

Sources:

The Farmer’s Allminax

The San Francisco Examiner

The Great Josh Billings RunAground

The Vault at Pfaff’s, An Archive of Art and Literature by the Bohemians of Antebellum New York

Santa Cruz Daily Surf

Omaha Daily Bee

The Monterey Argus

The Santa Cruz Sentinel

The Monterey Californian

The (Oroville) Weekly Mercury

“Cannery Row,” John Steinbeck

Well done! So many things I didn’t know and entertaining.