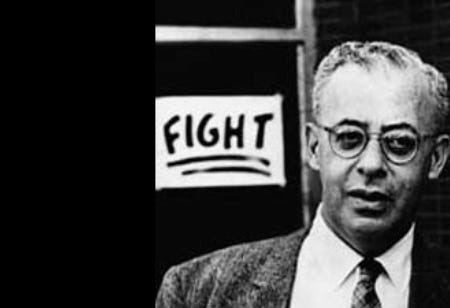

I’ve been thinking about Saul Alinsky lately. Maybe it’s the times we’re living in. Maybe it’s my inner revolutionary pirate yearning to break free.

Whatever it is, I was reminded recently that Alinsky, who wrote the textbooks on practical radical organizing and who pissed off all the right people during his colorful life, died on the mean streets of Carmel. (Alinsky’s death is Exhibit #1 that proves the only true thing I ever learned about Carmel during my meager years working as a reporter at the Pine Cone: You never know who’s going to drop dead there.)

Carmel ‘s storied past was more than a bunch of freaks who first planted their brand of bohemian bonhomie on the place and made it precious.

After the two-bit poet/realtors and florid authors cleared out of town, a subclass of aging and vaguely dangerous leftists started to hang out in Carmel. Take Lincoln Steffens, for instance. Steffens was a high-profile muckraking advocate for revolution against the capitalist overlords of his time. He found Carmel the perfect hideaway to write his autobiography, and he stayed there until he succumbed in 1936.

You’d never expect Lincoln Steffens to be the type of guy who would be caught dead in Carmel, but he was. Not only that, but the citizens of Carmel seemed to love the old leftist, maybe because he didn’t seem that dangerous anymore in his dotage.

Saul Alinsky arrived about 35 years later, finding a home in the Carmel Highlands, which he left to his ex-wife after their separation. By then he was regarded as an accomplished organizational genius among social justice warriors. He seeded community groups in Chicago, Buffalo and Rochester. He worked with communists and radicals to fight discriminatory labor and housing practices. He wrote books with titles like Reveille for Radicals and Rules for Radicals.

Jacques Maritain, the French philosopher, once called Alinsky “one of the few really great men of this century.”

Alinsky wasn’t a flamboyant man but he found ways to attract attention. He was hated and feared by the sorts of people who specialize in hate and fear. Wherever he went to organize local activists, the powers that be and their newspaper lapdogs signaled warnings that the agitating rabble-rouser was in town.

For instance, according to legend and lore, when the council of Bay Area Presbyterian Churches invited him to Oakland to help organize black neighborhoods, the panic-stricken Oakland City Council introduced a resolution banning him from the city. That resolution reportedly included an amendment to send Alinsky a 50-foot length of rope with which to hang himself. In response, he sent the council a box of diapers. Then he crossed the Bay Bridge accompanied by a phalanx of reporters and TV cameramen, waving his birth certificate and a U.S. passport as he passed a posse of flummoxed police officers.

While a champion for social justice with a genius for community organization, Alinsky was frustrated with complacent institutional liberals and the idiotic internecine political battles that needlessly divided like-minded intellectuals. He argued that change is only possible with radical organization.

“Society has good reason to fear the radical,” he wrote in Reveille. “Every shaking advance of mankind toward equality and justice has come from the radical. He hits, he hurts, he is dangerous. Conservative interests know that while liberals are most adept at breaking their own necks with their tongues, radicals are most adept at breaking the necks of conservatives.”

I also appreciate his observation that humorless radical organizers are their own worst enemies, and an impediment to progress. “Humor is essential to a successful tactician, for the most potent weapons known to mankind are satire and ridicule,” he wrote.

So it’s small wonder that he ran afoul of the student-led revolts of the 60s, filled as they were with humorless fire-breathers who apparently believed he wasn’t serious enough — or “pure” enough — to be much use to the cause. In fact, he publicly criticized the bomb throwers of the era who believed that radical change for justice could only be achieved “from the barrel of a gun,” which he called “an absurd rallying cry when the other side has all the guns.”

At one point, he offered the following advice to young progressives seeking substantive change:

“Do one of three things. One, go find a wailing wall and feel sorry for yourselves. Two, go psycho and start bombing — but this will only swing people to the right. Three, learn a lesson. Go home, organize, build power and at the next convention, you be the delegates.”

In other words, work within the system to affect radical change.

Alinsky had his strident adherents, most notably the community organizer Fred Ross, who worked with and inspired the work of Cesar Chavez.

Alinsky was still relevant enough in the 1970s that Playboy magazine published a 24,000-word interview with Alinsky. The interview gave him a chance to explain his pragmatic recipe for radical change. He also told Playboy he would next start organizing America’s white middle class to achieve positive social changes. The white middle class was a natural target, he claimed, “for the simple reason that this is where the real power lies.”

It’s one of the tragic ironies of American politics that right-wing Tea Party dweebs who despised Alinsky’s leftist sensibilities eventually and successfully employed his radical rules for organizing the white middle class after his death, while progressives spent their energies beating up one another for their failures to adhere to idiotic purity tests.

A couple of months after the Playboy interview, Alinsky was tending his ailing ex-wife, Jean Graham, in Carmel Highlands. He drove into town to run an errand on June 12, 1972, and collapsed on the sidewalk at San Carlos Street and 5th Avenue after suffering a fatal heart attack. He was 63 years old.

Subscriptions are free, but you may treat me to a coffee via my Ko-Fi page if you’re in the mood. I get my coffee at East Village.