The first ballplayer from Monterey County to play for the New York Yankees was a fiery, headstrong young man with enough raw potential to become one of baseball’s greatest early legends, on par with Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, Walter Johnson and other contemporaries of his era.

Harry Wolter was also a rarity in baseball, an accomplished pitcher with hitting skills and defensive abilities that kept him in the daily lineup on days he didn’t pitch. In that regard, he was an early-day version of Shoehei Ohtani, one of those do-everything talents who could pitch a shutout every fourth game and hit with power on the days between. Coaches and sportswriters in the early 1900s said Wolter was one of the best-looking ballplayers from the West Coast, a young talent destined for stardom.

Wolter played 110 years ago, in the dead-ball era when coaches, trainers and numbers-crunching analysts weren’t paying attention to a player’s every movement, needs and physical conditioning.

His career also spanned a period when agents weren’t looking out for the players’ best interests against the greed and whims of baseball management. Wolter was on his own, and his own stubborn nature undermined what might have been a sterling Major League legacy.

His Big League playing days were cut short by a string of injuries, illnesses and a dead left arm gone limp after throwing too many fastballs. His legacy is largely forgotten due to a fits-and-starts career made all the worse by his insistence that team owners should pay him what he knew he was worth. Always an advocate for his own skills, Wolter lost years of Major League service during the prime of his athletic life because he held out for more money, opting to play elsewhere when Big League owners weren’t willing to meet his demands.

The result of his obstinence was “more than a few unkind words and belaboring of contracts that certainly impacted his career in some fashion,” according to baseball analyst Bill Thompson.

Despite Wolter’s great potential and a handful of good years as a New York Yankee at the turn of the last century, his Major League experience was largely ignored when his obituaries were written in 1970. By then he was better known as a long-time Stanford University baseball coach who managed the team to its first league championships starting in 1924.

THE PRUNE PICKERS AND BEYOND

Wolter was the youngest of seven children, born in Monterey on July 11, 1884. He was a fourth-generation Californian with a pedigree in the state dating back to the late 1700s, the heir to a member of the original De Anza expedition. His great-grandmother, Maria Isabel Marcela Estrada, was born at Mission San Carlos in Monterey in 1789. He was raised on Van Buren Street, the son of a stable keeper in Monterey named Manuel Adolfo Wolter and his wife, Lucretia Wolter (née Little). Harry Wolter attended Monterey High and was a 1906 graduate of Santa Clara University, where he was a star ballplayer.

He first started playing professionally in 1905 when, at the age of 20, he pitched several games for the San Jose Prune Pickers. It was a ragtag team of professionals in something called the California State League, an “outlaw” league not affiliated with mainstream professional ballclubs.

A year later Wolter pitched for the Fresno Raisin Eaters of the Pacific Coast League. (And, sure, if San Jose could have the Prune Pickers, Fresno could certainly have the Raisin Eaters.) Despite an abysmal 12-21 pitching record for the abysmal Raisin Eaters, he did hit a solid .307 while he appeared in 149 games. The Los Angeles Times was impressed enough by Wolter that it reported he “has no bad habits” and would be “a good man for some big team to land.”

Sure enough, in 1907 he made his major league debut, with the Cincinnati Reds. Wolter would be the first Monterey County resident to play in a Major League ballgame. He wasn’t long for Cincinnati, though, and ended up in a Pittsburgh Pirates uniform, where he pitched two innings in a single game before finding himself in St. Louis, throwing for the Cardinals. He didn’t especially impress the Cardinals coach with his pitching (he was 0-2 with a 4.30 ERA), but he showed promise at the plate, hitting .340 in limited appearances as a rookie. In fact, Wolter’s ability to hit was one of the few bright spots on a team that finished with a record of 52 wins and 101 losses.

During that first season, Wolter played for three different teams, threw a total of 25 innings and had 69 plate appearances. Not an auspicious start to any Major League career.

St. Louis sold his contract to St. Paul in 1908, but Wolter refused the assignment. Instead the left-hander returned — defiant — to San Jose. There he was a Prune Picker phenom as both an outfielder and a pitcher, batting .339 while winning 24 games in 26 decisions on the mound. During one stretch, he recorded 17 consecutive wins.

He was signed by the Boston Red Sox the next year, but even then he insulted the baseball establishment by praising the outlaw California league. In a thinly-veiled swipe at the Big League owners, he told a sportswriter that operators of the outlaw league make “a studied effort” to “anticipate a man’s every want. There isn’t a single thing the most exacting player can ask for that isn’t granted before it is requested … It isn’t for love for the ‘outlaws’ that holds the players out there. It is simply the magnificent way they are treated.”

League officials, not amused, required that Wolter pay a $50 fine for failing to report to St. Paul in 1908 before he could resume his Big League career.

EARLY BALL IN THE BIG APPLE

The sports pages in most American newspapers carried ongoing accounts of Wolter's movements. They chronicled his refusal to return to St. Paul. They described his successful season in the outlaw league and his return to the Big League.

For the average baseball fan at the turn of the last century, before electronic media and sports talk radio, the hackneyed prose of besotted sportswriters brought games and players to life. The first live radio accounts of ball games weren’t broadcast until the 1920s, about the time Wolter retired. Newspapers built up the drama and the shmaltzy romance for the sport. Baseball stories were mostly puffery and bullshit.

Big city newspapers published second — or third or fourth — editions so they could be the first on the street with final scores. Sports fans in the 1900s knew Harry Wolter; they could identify his outsized ears and his freckles from the fanciful photo illustrations they’d seen in the papers. They knew from what they read that he was full or talent and feisty temperamental.

Fans in Boston anticipated a great season from Wolter in 1909. Unfortunately, his much-anticipated return to the Big Leagues fizzled. He had a so-so year for the Sox, hitting a measly .240 and finishing with a 4-4 pitching record.

The Red Sox sold his contract to the New York Highlanders (later to be known as the Yankees). Right off the bat, coaches in New York announced that Wolters’ pitching days were over, that they would let him concentrate on hitting and defense. It paid off, as he added twenty points to his batting average, while he scored 84 runs and drove in 42 as the lead-off hitter in 1910. The Highlanders finished second in the American League that year.

The team played its home games out of the rickety Hilltop Stadium, built atop a rock pile in Manhattan. With a seating capacity of 15,000 and a view of the Hudson River, author Thomas Wolfe once wrote that there was no place like it, “no place with an atom of its glory, pride and exultancy.” That was before the great baseball temple, Yankee Stadium, opened in 1923. The site of Hilltop Stadium is now used as a hospital. So it goes.

Back on the West Coast, Wolter’s friends were thrilled about his success. Throughout his career, the local newspapers reported his accomplishments and his movements. Getting signed with the New York team was the pinnacle. “Harry Wolter … is lambasting the life out of the ball these days,” the Monterey New Era reported, proudly reprinting a story from the New York Globe. Since moving to New York, “he has aroused a great deal of disturbance in the big league baseball society.”

Despite his many highlights during the 1910 campaign, Wolter may have been best known that year for misjudging a line drive off Ty Cobb’s bat and breaking his finger trying to catch it. Nevertheless, his 1910 and 1911 seasons in New York were the best of his Major League career; he hit a combined .284, scored 162 runs and stole 67 bases.

Oddly, Wolter decided to coach the Santa Clara University team in 1912, apparently “retiring” from play. But he got off to a rocky start after he suspended his star center fielder early in the season. According to press accounts, the player missed a spring practice to attend a dance in honor of his fiancé. The hard-assed Wolter considered a breach of commitment to the team and asserted his authority by imposing the suspension. The university’s president intervened, lifted the suspension, and Wolter resigned before the season even started started.

So Wolter returned to the Highlanders that year, to the relief of fans in New York. Wolter had been a solid contributor during his first two years with the team, and he was considered important to any future success. Unfortunately, he broke his leg in two places while sliding into second base on May 18, and he returned to Monterey to mend.

The following year, the Highlanders were known as the Yankees, and Wolter returned to wear the pinstripe uniform. But he was still hobbled by the bad leg, got into only 127 games and his batting average dropped to .254.

HOLDING OUT IN LOS ANGELES

Wolter was expected to report for duty with the Yankees in 1914. Instead, the New York team released him to the Los Angeles Angels. The Angels weren’t a Major League team (the Major Leagues had no presence in any city west of Saint Louis at the time). Wolter was furious, telling Sporting Life magazine that he had been railroaded. He complained that the Yankee owner at the time, Frank Farrell, had never given him a chance to find another Major League team to play for. “I will sign with the Angels for the same salary I received from the New Yorks,” he said, “but I will not accept any contract which calls for a cent less.”

While in San Francisco to play the Seals, Wolter took advantage of an off day, April 20, to marry a “society belle” from Palo Alto named Irene Hogan at St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church in Palo Alto. The San Francisco Chronicle reported the wedding was the "culmination of a childhood romance." The Examiner noted that the wedding ceremony was a surprise to the couple's friends. Hogan was a "musician of considerable talent and is a favorite among the younger set of the college town," according to the Examiner.

Wolter ended up playing for the Angels for the next three seasons. And while the Angels weren’t the Big Leagues, he had some of his best years ever in L.A. Through it all, the sportswriters speculated about his return to New York or some other Big League city.

He ended up playing for the Chicago Cubs in 1917, but his production was so-so for a team that finished fifth in the National League. A wire story floated around sports pages across the country that something wasn’t right with Wolter. “His past career — in the majors as well as on the coast — indicated that he would hit right around .300 for the Bruins,” according to the story. “Instead, he is hitting practically nothing.” Another wire story declared that Wolter was “finding National league pitching far more difficult than the brand delivered in the Pacific Coast league.”

The next season, the Cubs wanted to cut his salary by $1,300, so he returned the contract unsigned. That same year, his father died and he told friends attending the funeral that he would likely retire from baseball. He said he had landed a job at Standard Oil, in Taft, and that his pay was equal to anything he had earned playing baseball.

But baseball was in his blood, and he started scouting around for coaching jobs; he made no secret that he wanted to lead the Sacramento Senators of the PCL. He didn’t get the job, but the Senators did sign him to play the outfield. He kicked around for the next couple of years, playing for PCL teams in Seattle, San Francisco, Salt Lake City and Sacramento. He supplemented his income during those years working as a truck driver and a laborer for oil companies.

In the end, Wolter played seven Major League seasons for six different teams between 1907 to 1917. He lost at least four of his prime years playing for teams in California because of disagreements about his contracts, and his production in the Major Leagues was further curtailed by injuries and illnesses.

A LEGACY AT STANFORD

Finally, in 1923, he was hired to coach at Stanford, where he remained until 1949. Soon after his hire, the Stanford Quad reported that Wolter’s experience as a professional player is making a difference to the college team and that “he has insisted upon strict obedience and faithful work, with the result being a better working spirit than has been seen for many seasons.”

Indeed, Wolter brought discipline and professionalism to the Stanford game, and the team won its first league championships under his leadership.

Wolter also became a self-appointed ambassador for baseball, setting up barnstorming tours for his teams to faraway countries to introduce the game with exhibitions, lectures and quick coaching sessions. His Stanford team played games in Tokyo in 1926, and in 1928 the team sailed to Australia, New Zealand and Hawaii for games with local universities.

Notably, he coached the American team that played an exhibition game during the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. Originally scheduled to play Japan, the Japanese opted out so the Americans split its roster. The event was promoted in an effort to promote "America's game" as a permanent Olympic sport.

About 90,000 curious international sports fans watched the game in Berlin’s Olympic Stadium on Aug. 12. Correspondents at the game reported that the spectators were “bored, dazed and baffled” by what they saw, and by the fourth inning “the parade for the exits had become a stampede.” Baseball might have been a bust in Berlin, but Wolter made the most of the experience; he collected an Olympics belt buckle, a “participation medal,” and an autograph book filled with signatures from notable athletes at the games, including Jesse Owens, who famously foiled Adolph Hitler with his presence in Berlin that year.

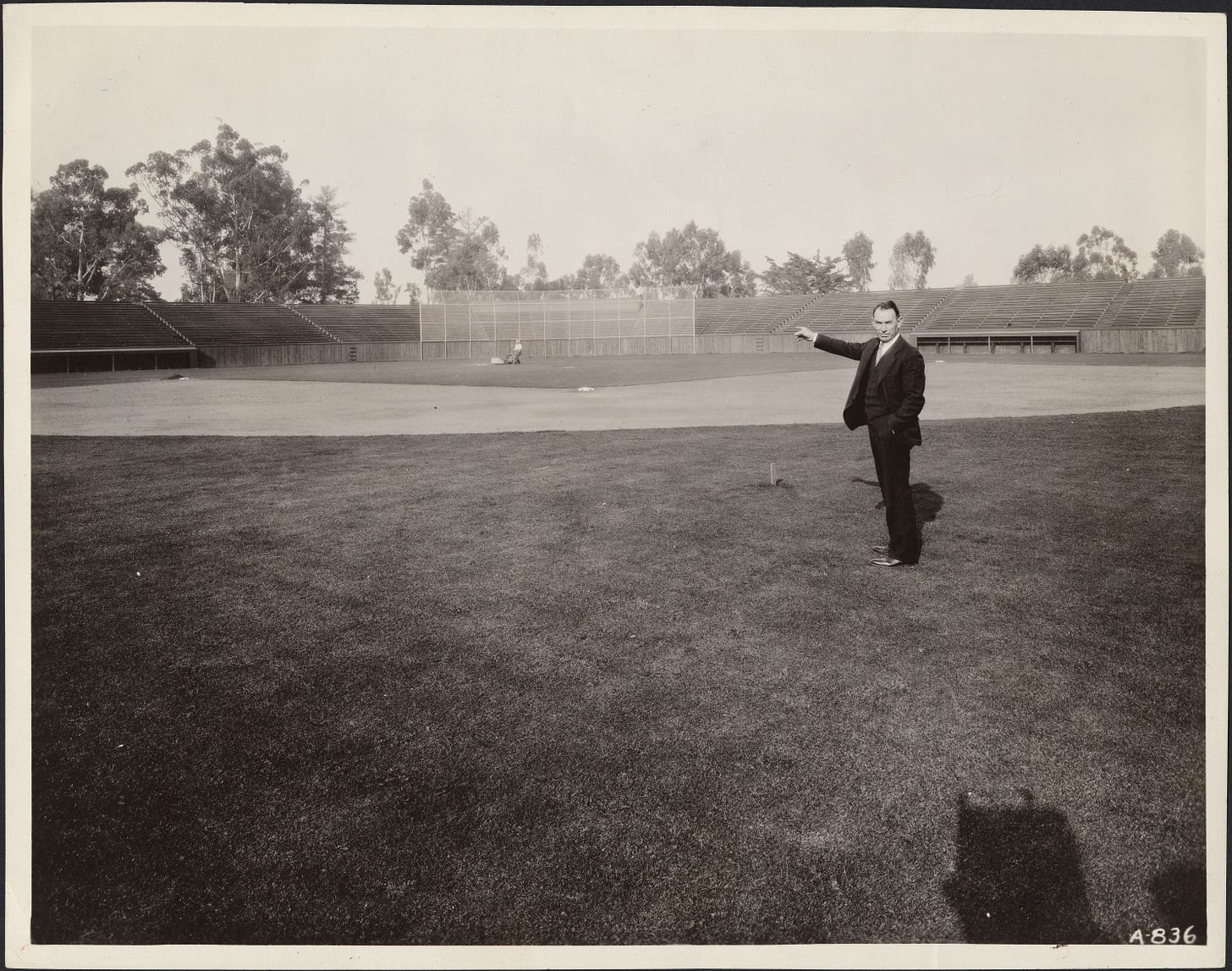

When Wolter retired from Stanford in 1949, more than 100 of his former players showed up for “Harry Wolter Day” at Sunken Diamond, the Cardinal ballpark he designed and dedicated. During the celebration, Wolter took a couple of swings against former Major League pitcher Ernie Nevers. Wolter reportedly did well, “lashing out several long blows,” according to one account.

Wolter died 21 years later, at the age of 85, in a house on the campus that he and his wife moved into when he first took the job at Stanford. He and Irene had no children. After a funeral at the Mission Chapel at Santa Clara University, his body was entombed at Hollister Catholic Cemetery.

Though he had been an original Yankees, his death rated a mere three-sentence mention in The New York Times obituaries page.

“It’s obvious Wolter truly loved baseball … but he was also a shrewd businessman that held out on contracts and was willing to walk away from the sport,” said Wade Wolter, a fan from Illinois who spent years researching the career of the old Major Leaguer. His study of the ballplayer was spawned by their surnames, and he wondered if they might be related. His research resulted in a fansite dedicated to Harry Wolter. “I always have gotten the vibe that he loved playing and coaching the game immensely but understood that it was an open door to a career that could earn him security and a good living.”

Stanford baseball trivia: The current coach for the Stanford Cardinal baseball team, David Esquer, is also from Monterey County. He attended Palma High School and played for Stanford from 1984 to 1987.

Sources:

Library of Congress

The Huntington Library

Stanford University Athletic Department

Harry Meiggs Wolter: One Man’s Life in Baseball, by Wade Wolter

Baseball Almanac

The New York Times

Harry Wolter, by Bill Nowlin, Society for American Baseball Research

Santa Clara University Athletics’ Bronco Bench Foundation

Bridging the Two-Way Gap: Harry Wolter, Words Above Replacement, by Bill Thompson

The Stanford Daily

The Baltimore Sun

The Carbondale Daily News

The Fresno Morning Republic

The Sacramento Bee

The Dayton Daily News

The Monterey Daily Cypress

The San Francisco Examiner

The San Francisco Chronicle

The (Brooklyn) Times Union

The Santa Cruz Evening News

Wow, Joe, that was a great story. As a lover of baseball, during this World Series time (even though I want both teams to lose), it was timely, well researched and, most importantly, well told. Thank you!